Who Dares Wins: Britain, 1979–1982 : a review

- The Beagle

- May 29, 2020

- 5 min read

Who Dares Wins: Britain, 1979–1982

Dominic Sandbrook, Allen Lane, 2019, ISBN 978 1 846 14747 1, 900pp

A hefty but enjoyable tome; the hardback version weighs in at 1.62 kilograms.

a review by Trevor Moore:

A book of over 900 pages that covers 3 years is reading material is not to be enterprised lightly and it was with some trepidation that I started to read it. My mother left me with enough of a sense of possibly misplaced responsibility to believe that if you have bought a book then you should read it all. It’s a bit like her admonition that I should eat all my dinner. The reason I am writing this review is not because the period (1979–1982) is particularly significant and even less because I think that this period of British history has much, if any, relevance to Australia. Of course, it is an interesting period because it ends with the events that led to the Falkland War. But it is also interesting because of what it tells us about the period we are living in today.

I have an 18-month-old granddaughter who in 60 or 70 years’ time, at the end of this century, will be able to say to her grandchildren that she lived through the great plague of 2019–20. She will have no recollection of what it was like, but she will have some credibility for having lived through it. I lived through Thatcher’s Britain of 1979–1982 when unemployment in the UK reached staggering levels. I am not sure that gives me any credibility, but as I read Sandbrook’s book I realised that many of the things that seemed important then, do not seem important now even if I remembered them. I can remember high unemployment in general terms, and I can recall a disastrous budget in 1979 that took aim, in part, at an 83% top rate of tax. I can remember the British Leyland problems and Ken Livingstone but as for the detail, I could have recalled little of it.

So, it is with the events of today. Over the last few weeks the news has become, in my view, unremittingly tedious and uniform. It’s all about one topic. It’s as if the world has stopped. But the world has not stopped; humankind continues on its inexorable march to whatever future it might stumble upon. There will be many books about the coronavirus pandemic, but none will be worth reading unless it is published after about 2050, and by then I probably won’t be around to read it. But its readers will recall the events of 2019-2020, which they too will have forgotten, because humankind just carried on. History as a whole is important even if individual events may be less so. What I gleaned from Dominic Sandbrook’s book is that, however important it seems to be now, it probably isn’t that important when all is said and done.

Having said all that, this book is a great read though I am not suggesting that you should read it unless (a) you have strong arms because it weighs a lot and (b) you are vaguely interested in its subject matter. Dominic Sandbrook is a well-known historian of modern history. He taught at the University of Sheffield before becoming a full-time writer. One would like to meet any writer who can maintain a focus on a short period of history and produce over 900 pages describing that period. I now have on my reading pile an earlier book of his, White Heat: A history of Britain in the Swinging Sixties. This is also over 900 pages. He is clearly a man of detail and perhaps, if I did meet him, his attention to detail would outlast my attention span. There is no bibliography in this book but there are 60 pages of notes in a very small font size. These notes suggest that much of what Sandbrook writes is drawn on contemporary and popular accounts; newspapers, magazines and especially a mass observation project that was launched in 1981 as a “national life writing project”.

Dominic Sandbrook has trawled through yards of this stuff. He is a committed writer indeed.

The period 1979-1980 saw the introduction of the BBC Micro Computer that radically and dramatically changed our views about what a computer was and what it could do. There were other personal computers around at the same time - the Commodore PET and the Sinclair ZX - but none came close to the BBC Micro Computer. This was made by a company called Acorn who were hopelessly under-resourced and under-prepared for the demand that followed. It was remarkably prescient of the Thatcher government to support the whole computer initiative of the late 70s and early 80s. After all this was a period when The Guardian felt that it could write on 10 September 1981:

“Do you actually need a computer? Is the computer a panacea, a plaything, a workhorse, a job destroyer, a profit maker, a job creator, or the overblown puff of a marketing manager's imagination?”

I suppose we know the answer to that now. The National Archives of Australia note that, under Malcolm Fraser’s prime ministership “the first personal computers went on sale. Thirty years earlier the first mainframe computer, UNIVAC, had come into use.” Christopher Evans’ 1979 book The Mighty Micro proclaims on the dust jacket “a twenty-hour working week and retirement at fifty … a front door that opens only for you and a car that anticipates danger on the roads … a wristwatch which monitors your heart and blood pressure … an entire library stored in the space occupied by just one of today's books … Science-fiction? No, for by the year 2000 all this will be part of our everyday lives.” Apart for the 20-hour week and retirement at 50, he was pretty close. But not many people believed it.

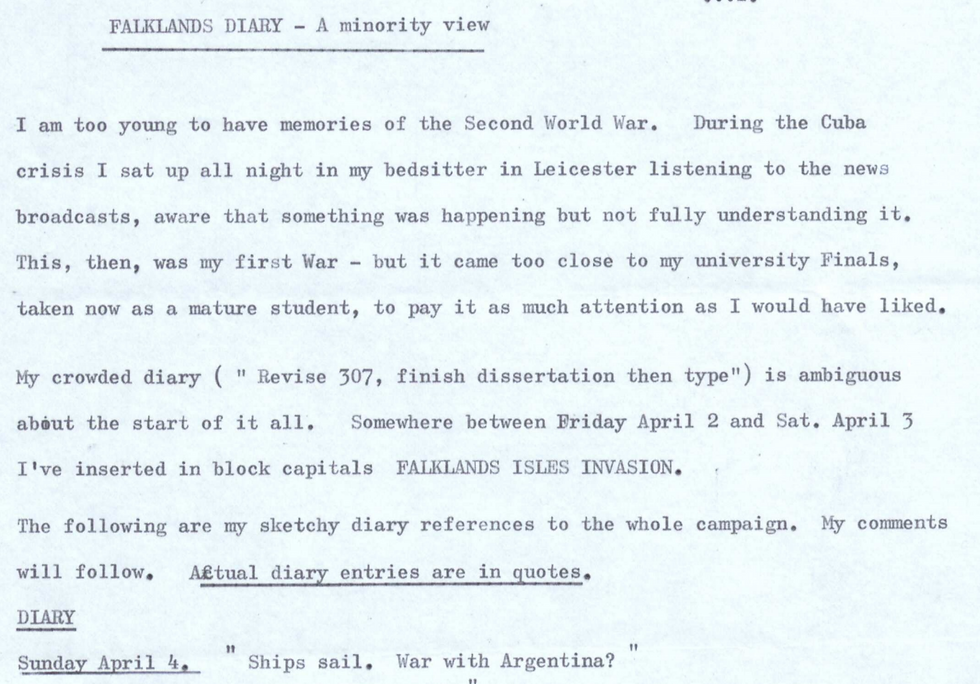

I do remember when the Falklands were liberated or invaded, depending on your point of view. Sandbrook devotes the last three chapters of his book to the events that surrounded the Falklands episode. My recollection are of almost universal support, myself included, for the actions of the government. But reading the book I learn that there was not universal support and the government was not as clearly decided upon a course of action as we thought at the time. Many people felt that the whole episode was, again according to The Guardian, a “bizarre spasm of post-imperial imperialism” that was talked up by the populist press. Sandbrook points out that it wasn’t the Falklands war that drove the economic improvement of the 1980s; that was happening anyway. But there’s nothing like a succesful war to make a leader look good.

With the benefit of hindsight, perhaps it was all jingoistic rhetoric.

You would read this book only if you have the stamina for 900 pages and only then if you are interested in the period and the country. But having read it, I have to say that it has given me a sense of perspective about what really matters. And what really matters is not the politicisation that happens today (and in 1979-1982) of so much public debate. What matters is the social fabric of the place that we live in. Pretty much everything else is ephemeral.