Batemans Bay Heritage Museum : Cook 250 years on

- The Beagle

- Apr 22, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 22, 2020

April 22nd marks the 250th anniversary of the naming of Batemans Bay

Batemans Bay Heritage Museum is proud to be hosting a new exhibition, 'Cook and the Pacific', presented by the National Library of Australia, Canberra.

Although the Museum's physical exhibition is closed due to Covid-19 isolation, comprehensive extracts are available online.

Go to www.batemansbayheritagemuseum.com and the special Cook250 page for details of the Endeavour's first voyage, Cook's 'secret instructions', and the scientific outcomes.

Captain James Cook is an enigma.

A complex and almost mythical figure in history. His legacy is mixed. For some, he is the great navigator, cartographer, and explorer. For many First Nations peoples across the Pacific, Cook symbolises centuries of dispossession which still resonate powerfully.

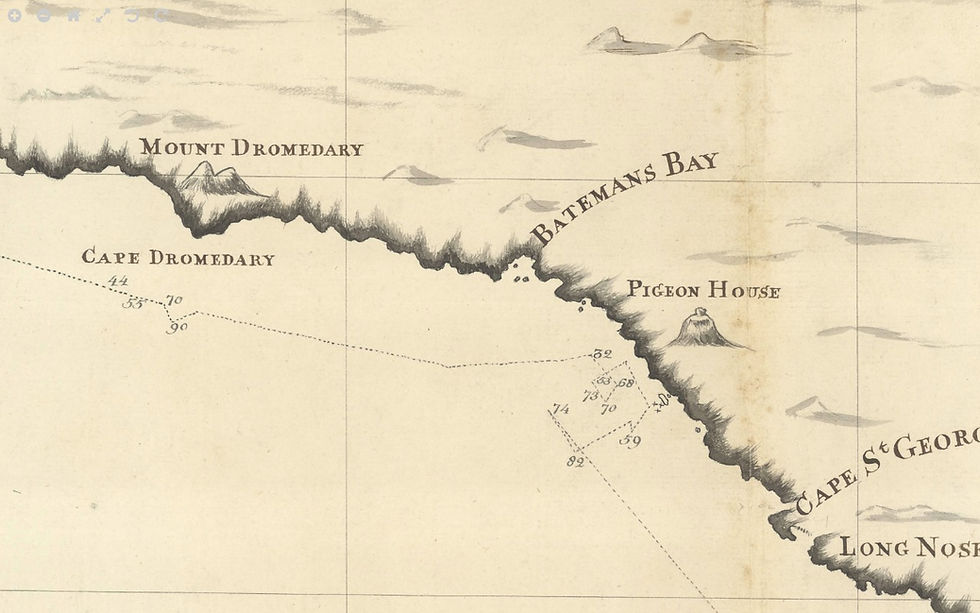

April 22nd marks the 250th anniversary of James Cook's exploration of the south east coast of ''New Holland', specifically arriving off what is now Eurobodalla On this first voyage of discovery to the Pacific, Cook retained the usual 'explorer's naming rights' though he rarely honoured individuals, preferring descriptive landmarks like Mt Dromedary (Gulaga) and Pigeonhouse (Didthul). Bateman Bay was an exception.

Above: From a high resolution scan of Cook's chart of the south east coastline available from the University of Wisconsin. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/1090/rec/5 The struggle between the French and British for control of Canada was part of a conflict, known as the Seven Years War, involving all the major powers of Europe. Cook and Bateman were career naval officers who took part in this 'age of sail' war at sea. Subsequently, Bateman was in command of the Northumberland, ordered to survey the St Lawrence river and Canadian coastline. Cook was ship's master on board; a gifted surveyor himself, the two men produced charts considered to be amongst the finest examples of coastal cartography of the period, jointly signed by Bateman and Cook. This respected colleague was the man Cook honoured by naming a distinctive feature his journal describes as 'an open Bay wherein lay three or 4 small Islands bore NWBW distant 4 ^5 or 6 Leagues this Bay seem'd to be but very little shelterd from the sea winds and yet it is the only likely anchoring place I have yet seen upon the Coast.’

WHO WAS THE BATEMAN of BATEMAN’S BAY?

Nathaniel Bateman was an experienced British naval officer for whom James Cook had considerable respect. Bateman began his career at 14 as an ordinary seaman, gaining his first promotion for exceptional gallantry during a sea battle off France.

He was commissioned Lieutenant in 1756, appointed a Commander in 1759, and commissioned Captain in 1760. As a younger man, Cook had served under Bateman aboard the survey ship Northumberland, producing charts of the St Lawrence River and the Canadian coastline.

These charts are considered to be amongst the finest examples of coastal cartography of the period and are jointly signed by Bateman and Cook. This was the man Cook honoured by naming a distinctive feature whilst charting of the south coast of NSW.

Destruction of the French Frigates Arianne and Andromaque 22nd May 1812. The image shows the last stages of the battle, Northumberland in the forefront. Bateman began his career at 14 as an ordinary seaman, gaining his first promotion for exceptional gallantry during a sea battle off France. He was commissioned Lieutenant in 1756, appointed a Commander in 1759, and commissioned Captain in 1760. Twenty years later he would be unfairly and brutally dismissed. His first command was that of the 20-gun Euros. The Euros was one of a line of British ships involved in the siege of Quebec in 1760. The struggle between the French and British for control of Canada was part of a conflict, known as the Seven Years War, involving all the major powers of Europe. The French eventually withdrew from Quebec after a lengthy barrage from the British fleet and an intensive winter ground assault. Most of the city had been destroyed. The Euros had been wrecked in the St Lawrence during the campaign, but with no loss of life. Bateman was given another command almost immediately. The Northumberland was a warship of 70 guns that could carry a complement of 500 men. It had been used against the French but now, under Bateman, was assigned to undertake survey work. On board, in his third year as Master, was James Cook. Shortly after leaving the St Lawrence River to commence detailed coastal mapping, Bateman was ordered to join with other ships to intercept a small French force attempting to take possession of the port town of St Johns, Newfoundland. Both fleets passed each other in the fog and not one cannon shot was fired. Within months came the news of the fall of Havana to the Spanish and Bateman was ordered to sail for home. James Cook then left the ship to continue his survey career elsewhere. Captain Nathaniel Bateman’s next command was the 44- gun Ludlow Castle. Bateman sailed the ship with a full naval compliment to join with others protecting British interests in Africa and the West Indies. The Ludlow Castle spent most of its commissioned life in the Caribbean. Bateman was given orders to capture the notorious pirate John Smith, responsible for looting and sinking many ships in the area. Smith evaded capture but was imprisoned and hung some months later. After the Ludlow Castle, a dozen years were to pass before Bateman’s third commission. Like his previous command, the Winchelsea was a fifth-rate warship of 32 guns. It too spent most of its life in the Caribbean, later to become a troop carrier and finally a prison ship. 1776 found Bateman in the middle of the American War of Independence. His role in the Caribbean was to attack American ships as well as those of the French and Spanish who were aiding the Patriots. Bateman’s first prize was the Will and Henry, a South Carolina privateer schooner, captured while transporting a cargo of sugar and rum. Next came the American raider Revenge, this time with a cargo of “gunpowder, shot and dry goods”. Two years later, Captain Nathaniel Bateman received a significant career promotion with the command of the impressive Yarmouth. The Yarmouth, bristling with 64 guns and carrying a crew of 450, was one of a number of warships in a fleet of 21 under the overall command of the controversial Admiral George Rodney. In July 1979, Admiral Rodney ordered the English fleet to attack the French at Granada. The assault was impulsive and uncoordinated. The Yarmouth was separated from the main body and took little part in the action. Captain Nathaniel Bateman’s next battle would be with the bureaucracy of the British Admiralty. Admiral Rodney had ordered that Bateman be court martialled. By 1779, Captain Nathaniel Bateman was still a young man at the peak of his career. The Yarmouth was one of 21 ships-of-the-line protecting Britain’s political and commercial interests in the West Indies. The American War of Independence had drawn Britain’s traditional foes into the conflict with the French and Spanish providing military and supply aid to the Patriots. Admiral George Rodney was the overall commander of the British Caribbean fleet. He was considered a brilliant naval tactician famous for his aggressive techniques of breaking the opposition line. Rodney was militarily aggressive and politically ambitious. He demanded the total loyalty and commitment of all under his command. His goal was to achieve military glory to enhance his political ambitions. A controversial figure, he was accused of an obsession with prize money and power. Five years earlier, Rodney had used the wealth accumulated from capturing enemy ships on the high seas to purchase a large country estate and a seat in the House of Commons. Living beyond his means he ran up large debts and was forced to flee his creditors. He spent time in a French jail but was released after a large sum was paid on his behalf by a benefactor. He returned to Britain and was appointed to a new command. Like Bateman, George Rodney began his career at fourteen and was promoted rapidly through the ranks, developing a reputation for bravery and audacious close quarter combat manoeuvres. In July 1779, Rodney ordered his fleet, including Nathaniel Bateman’s Yarmouth, into a conflict with the French who had anchored off Granada. This major sea battle was fought under the command of a Rodney favourite, Admiral Byron. Byron, eager to impress his mentor, launched his attack by using Rodney’s preferred method of driving into the French centre. The attack was reckless and poorly controlled. Signals were misread or went unnoticed. Faster ships found themselves unsupported by the larger and slower moving warships. The battle was indecisive and both fleets withdrew. In London, the Admiralty established an inquiry based on reports by Admiral Rodney that certain commanders had not responded to direction. Three Captains of the Fleet were accused of “failure to do their duty during battle”. Rodney specifically criticised Nathaniel Bateman. As the battle commenced, Bateman had found his much larger and slower ship well astern of the leading attack. To compensate he changed course to engage from a different direction. The Yarmouth eventually re-entered the battle line only to have its mainsail shot way and to then drift away from the conflict. A furious Admiral Rodney turned on Nathaniel Bateman to divert criticism away from what had been a clumsy and poorly conducted assault. Bateman was arrested and held in detention for 6 months. Bateman requested that his trial take place in London where he was much respected and where he could count on considerable support. Rodney refused, saying that he would not send him home “to give play to the factions there”. He was eventually court-martialled for disobedience but the charges were only partly proven. Bateman was relieved of his command and dismissed from the service. The court recommended clemency and directed that the case be referred to the King. Bateman was subsequently returned to his rank but retired soon after and lived out his life quietly on the family estate. The London Advertiser at the time reported on Bateman’s distinguished career and observed, “much commiseration was felt for him”. Admiral Rodney was later severely criticised for his determination to punish Bateman, and the Admiralty viewed the court-martial “as a harshness bordering on cruelty”. Orders for Rodney’s recall were subsequently dispatched from Britain but had not yet arrived when he launched a timely and decisive battle at Les Saintes in 1782, shattering French naval strength in the West Indies. Admiral Rodney instead returned home a hero. He was awarded a peerage and lived comfortably until his death. Nathaniel Bateman’s son, Charles, also joined the British navy at the age of 14 and rose to the rank of Captain. His last command was a warship of 64 guns active in the Mediterranean. This information is courtesy of Kim Odgers, author of ‘Our Town Our People - A tribute to the men and women who shaped our town’.