Victory in the Kitchen: The Life of Churchill’s Cook - a review

- The Beagle

- Sep 5, 2020

- 4 min read

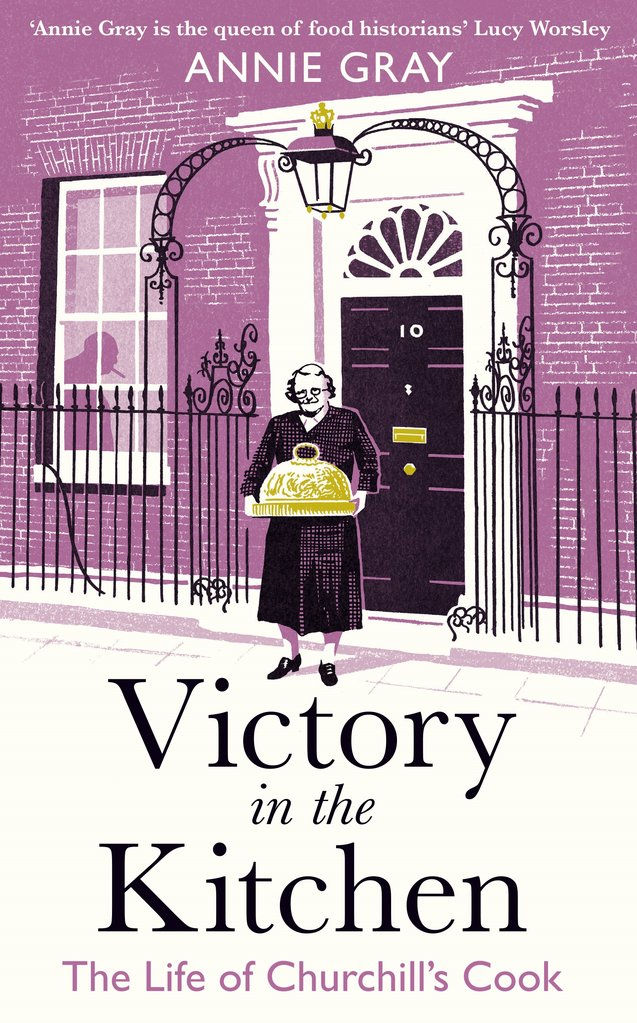

by Trevor Moore Victory in the Kitchen: The Life of Churchill’s Cook

Annie Gray, Profile Books, 2020, ISBN 978-1-78816-044-5, 390pp

There is a concerted effort by historians today to restore women to their rightful place in history. On my reading pile is Nicola Tallis’ Uncrowned Queen which is about Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII and grandmother of Henry VIII. She was a mover and shaker in Tudor times and largely unregarded until now. I am waiting for a biography of Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan who won the George Cross after being executed by the Nazis in 1944. She was the first female wireless operator to be sent from the UK into occupied France to aid the French Resistance during World War II. These are but two women whose contributions to history need to be written about and discussed.

The subject this review, Georgina Landamere née Young is another such woman. Though her contribution to history may seem more prosaic than either Margaret Beaufort of Noor Inayat Khan, that contribution was recognised by Churchill. She was born in 1882 in Hertfordshire and had she been a man she would have been head chef at any of the great London restaurants. She stared work at the age of 15 as a scullery maid and, having decided cooking was her thing, she worked her way up through the ranks. When she started she would rise at 0500 and go to bed at 2200. She would peel vegetables and scour pans in between those hours. Life was not easy. She carefully selected the people she worked for and as a result she became a leading society cook or, more properly, chef though she was usually refereed to as a cook. She married a Frenchman, Paul Landamere, in 1909 just two months after the death of his first wife. Landamere, who was 20 years her senior, was also a cook and they almost certainly met at a catering gig.

We do not now a great deal about the life of Georgina Landamere, notwithstanding this book. We might have had a fuller account of her life as she write an autobiography but her daughter and son-in-law persuaded her that it was not worth reading so she destroyed it. Her granddaughter managed to save 26 pages. You may wonder at this, as I did, but in the 1960s the idea of having been in service was as difficult as the idea of being “in trade” was to the Victorians. As a result, Annie Gray, who is a writer on the history of food and dining, uses what we know of Georgina’s life to look at the way domestic service changed in the first half of the 20th century and at the way food has changed in that time.

Through the people that she cooked for she had become acquainted with the Churchills and when the war broke out (81 years ago on 3 September 1939) she suggested to Clementine Churchill that she be their cook. Working for the Churchills was not easy. They were not easy people to get in with, though Georgina formed a very close relationship with Clementine. Cooking for them during the war meant moving between the kitchen in Downing Street, a kitchen underground in the Cabinet War Rooms and Chequers (the country home of the British Prime Minister). Flexibility was important: she never quite knew what time dinner should be nor how many diners there would be.

This is a fascinating book whether you are interested in food, in the history of domestic service, or in the Churchills. The book is peppered with recipes and one caught my eye. It reads like this:

½ lb butter beaten to a cream, 7 eggs, yolks & whites separated, ½ lb best chocolate grated and heated and then beaten up with the butter, with 8 oz sugar and 8 oz of dried flour and 4 oz ground almonds, and 1 teaspoon of sal volatile, bake in a slack oven.

It is the “slack oven” that got me. I decided to try this. As it happens it has an error in the recipe (at least there’s no way you could stir the batter with 8 ounces of flour).

Here’s what we did …

This cake is quite heavy and is less chocolatey than you would expect from 250 gms of dark chocolate. My daughter and I enjoyed it but my wife was less enthusiastic.

Ingredients

250 gms butter

250 gms dark chocolate, we used Lindt

250 gms sugar

125 gms flour (note the original says 250 gms, you could probably go to 90 grams)

125 gms ground almonds

7 eggs, separated

1 teaspoon baking powder (this is the modern version of sal volatile)

Method

1. Grease and line with baking paper a 26 cm springform cake tin

2. Grate the chocolate and melt in the microwave. Heat in 15 second bursts stirring in between. Set aside.

3. Cream the butter and sugar

4. Add the egg yolks and whisk together

5. Add the chocolate to the batter

6. Mix up the sugar, flour, ground almonds and baking powder and add to the batter

7. Bake at 150 – 160°C for 30 – 40 minutes until the middle of the cake is 95°C or check that a skewer comes out clean.

The resulting cake is about 3 cm high: you could make a higher cake with (say) a 22 cm cake tin.

Icing

We iced the cake with a blood orange frosting as follows:

90 grams unsalted butter, softened

100 grams cups icing sugar

1 tsp. vanilla extract

Zest and juice (about 30 ml) of a blood orange

Using a hand mixer, beat cream cheese and butter until smooth. With the motor running, slowly add sugar and vanilla; beat until smooth.

We grated orange chocolate over the icing and added little squares of orange chocolate. It would probably go with cucumber sandwiches with their crusts cut off.